‘Future is not a noun, it’s a verb.’

– Bruce Sterling

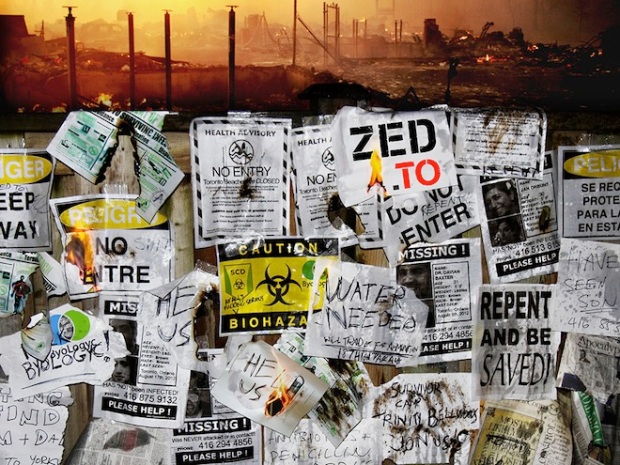

Image from the Mission Business’ ZED.TO

In the precis to the Australian Academy of Science’s 2011 book Negotiating our future: living scenarios for Australia to 2050, the Academy notes that, ‘The future is uncertain, contested, and ultimately shared.’

It’s a memorable phrase with serious implications, which is why I co-opted it for the title of this report. The writers go on to say:

‘The uncertainty of the future is experienced everywhere, from weather to politics to the fragility of human existence. The contestability of the future is also familiar, from struggles between people and groups of different convictions for control of choices about pathways. Yet as the future rolls inevitably into the present, multiple pathways and choices crystallise into actual events that form shared realities for individuals, communities and nations.’

The Academy’s members assert that we as Australian citizens have a fundamental right to contribute to the shaping of Australia’s future. Each of us must be able to share our vision for the country’s future, to speak and be listened to.

As they say: ‘Grappling with these realities is only possible through conversation, at national scale and over a prolonged period.’

However, as the Academy has pointed out elsewhere, at this time the only groups regularly engaged in forecasting and planning for Australia’s long-term future are politicians and private corporations.

This was the impetus for the series of public forums held as part of the Australia 2050 project over 2012-13, in which the Academy invited members of the public to take part in conversations about the country’s future and to share their views.

As valuable as those public forums were, it is not enough to simply have a platform where we can voice our innermost hopes and fears about the future; we need to be supported to help us use this opportunity effectively.

It is simple to respond emotionally to the events of today; it is extremely difficult to think constructively about the world 10, 20 or 50 years from now. For most of us it is difficult to critically and constructively imagine something so abstract, and public forums without careful guidance run the risk of losing focus and descending into platitudes.

If we non-specialists wish to contribute meaningfully to the shaping of Australia’s future, we need access to tools that can help us shape our thinking around this difficult topic.

We need frameworks and structures that can help us visualise the possible shapes of the world to come, and to help form our most deeply-felt opinions and dreams into tangible, achievable visions for a future Australia.

Critical tools for thinking about the future do exist. This is the domain of futurists, who over the last few decades have developed a sophisticated and varied set of strategies and methods to help us come to grips with the challenge of looking ahead.

Futures Studies is a field of academic research and a consultancy activity. There have always been futurists among us, but the field as it is today has its origins in post-World War II strategic think-tanks. Over the last fifty years, it has grown to encompass a wide range of approaches and ideals.

Across the spectrum of Futures Studies, though, there is one core principle: the future cannot be predicted.

As futurist Stuart Candy puts it: ‘The future does not exist. The ultimate reason to engage in futures work, then, and especially to create scenarios — which are merely tools to help us think — is to enrich our perceptions and options in the evolving present. More concretely, of course, it is an instrument for mitigating risks and finding new opportunities.’

Futures studies is an active process of identifying trends, contemplating possibilities and sketching scenarios. It’s a complex and multi-faceted field that draws on history, earth system sciences, politics and sociology.

What futurists provide is not a prophetic timeline of the years to come, but a range of scenarios that embody the different directions our society might go in. Futurists offer a sense of the consequences of our decisions and actions.

The value of this practice is not in the accuracy of any given future scenario, but from having a range of them, showing us the likely extremes and bounding our expectations.

As futurist Daniel Bell wrote back in 1967, ‘What is central… to the present future studies is not an effort to ‘predict’ the future, as if this were some far-flung rug of time unrolling to some distant point, but the effort to sketch ‘alternative futures’ — in other words, the likely results of different choices, so that the polity can understand costs and consequences of different desires.’

Students at the Hawaii Research Center for Futures Studies experiment with political sloganeering. Image thanks to John Sweeney.

Futurists use a range of tools and methods to generate forecasts of the future. Jim Dator of the Hawaii Research Center for Futures Studies says ‘Futures studies as an academic and as a consulting activity is based on the identification and analysis of images of the futures; theories of social stability and change; methods of social forecasting and design; the monitoring of continuing trends and the identification of emerging issues which might alter those trends or create new ones.’

Perhaps the definitive tool in the futurist’s kit, and the thing that distinguishes contemporary futurists from their historical predecessors, is the practice of generating multiple future scenarios.

Dator explains: ‘A forecast is intended to be a logical statement, a useful statement, about the futures. Futures thus are plural, alternative, diverse, possible… Thus we speak of possible “alternative futures” and not “THE future” as though it were a pre-existing entity “out there” waiting to be predicted.’

The futurists’ response to the impossible task of trying to anticipate the future is to generate a range of future scenarios, seeking to capture the spectrum of possibility and be prepared for whatever happens.

Futurists such as James A. Ogilvy argue that by adopting the ‘scenaric stance’ and holding multiple futures in view simultaneously, practitioners achieve a kind of emotional and intellectual maturity that is not available to either the simple optimist or the simple pessimist.

‘Yes, things could turn out badly. But, no, that is not in itself reason for inaction. Yes, things could turn out very well, but, no, that is not in itself reason for foolish bravado. By holding in mind several different futures at once, one is able to proceed deliberately yet flexibly; resolutely yet cautiously… He or she who sees no opportunities is blind. He or she who senses no threats is foolish. But he or she who sees both threats and opportunities shining forth in rich and vivid scenarios may just be able to make the choices and implement the plans that will take us to the high road and beyond.’

Although technically there is no limit to the hypothetical alternative futures we could imagine, in practice practitioners tend to limit their speculation to a few archetypal scenarios – typically, four: Continued Growth, Collapse, Discipline, and Transformation.

Jim Dator justifies this practice by saying, ‘Over the years, we have learned that all of the billions of images of the future that exist in the minds and actions of humans can be lumped into four “generic” images of the futures that serve as motivations for human individual and group behavior. Whenever we are asked, “so what is the future,” we reply, “there are four alternative futures.”

These four scenario archetypes are used by a majority of the world’s scientists; for instance, the International Panel on Climate Change’s report on the impacts of climate change depicts four possible future scenarios for the planet, depending on the rate of greenhouse gas emissions.

In practice, Futures Studies is a continuous process of forecasting alternative futures, envisioning preferred futures and identifying pathways to move toward them. Outside of academia, futurists are often employed by large corporations to look ahead and anticipate challenges and opportunities in the company’s medium to long-term future.

‘Futures studies is related to but different from planning and policy-making,’ argues Dator, ‘just as planning and policy-making are related to but different from day-to-day administration. Just as day-to-day administration should be guided by prior planning and policies, so also should planning and policies be guided by prior futures foresight activities.’

So, are the tools and methods of futurists actually applicable to people outside of academia?

I can see several clear benefits to our adopting some of the practices of futures studies in our everyday lives.

99c Futures. From the Extrapolation Factory website.

While the tools and techniques of future studies have been adopted by many corporations and policy-makers over the last two decades, there has been very little engagement with the wider public. People are often unaware that futurists exist, let alone understand what it is they do. The result is an unfortunate disconnect, which separates the public from the valuable tools Futures Studies offers to help us think about and plan for the future.

In the last few years, a convergence of ideas and practice has led to the emergence of a new way of doing futures, one that sidesteps intellectual discussion in favour of provoking more emotional responses.

A diverse selection of visual art, films, theatre performances, digital games and artistic interventions has been gathered under the banner of ‘Experiential Futures’. The term, coined by futurist Stuart Candy and adopted by Bruce Sterling, Anab Jain and others, refers to the practice of embodying elements of hypothetical future scenarios through visual media, film, industrial design, theatre and gaming.

The last two years has seen an increase in this kind of practice, which seeks to ‘de-abstractify’ how the future might look using the tools and techniques of the arts.

From large-scale participatory theatre works involving thousands of participants, to corporate videos promoting as-yet-nonexistent technologies, to ‘future artifacts’ installed as guerilla artworks in urban spaces, the Experiential Futures label includes work in any creative medium.

Procession for cyborg saint Santa Ste.la as part of the 2011 Lecturas de Cruce (‘Crossing Lectures’) on the US-Mexico border

The guiding principle connecting and underpinning these projects is the idea of manifesting some aspect of a hypothetical future in the present day. Rather than communicating ideas about the future verbally, practitioners seek to create an ‘experience’ of the future for their audiences / viewers / participants.

‘Given that future scenarios have no factual, “evidentiary” referents per se,’ says Stuart Candy, ‘Experiential scenarios and artifacts afford people the rudiments of a common vocabulary, a virtual shared experience, however basic, around which their contributions can cohere, and push off in discussion.’

From the futurist perspective, the intent behind these works is to prompt conversation or reflection around the idea of the future. The artistic intention, meanwhile, is to use Futures Studies ideas to generate works of art that are emotive and effective.

At its core, the practice of Experiential Futures is fundamentally inter-disciplinary. The artist needs the futurist’s insights and strategies of in order to meaningfully convey anything about the future. And the futurist needs the artist’s creative and design skills in order to convey those insights in an effective and accessible way.

One of the major challenges in creating an Experiential Futures work is to strike an effective balance between the ideas and the form. If the science is prioritised over the art, or vice versa, the work may end up either:

The only way to negotiate those difficulties is to dive in and begin.

Experiential Futures works have been produced since the 1970s, starting with The Great Hawaiian Jubilee, but one of the mot elaborate was the Hawaii 2050 event held in Honolulu in 2005.

Hawaiian state legislators approached the Hawaii Research Center for Futures Studies (HRCFS) about launching a broad-based public conversation around sustainability, focusing on the year 2050.

HRCFS staff Jim Dator, Stuart Candy and Jake Dunagan created a series of four experiential scenarios in different spaces throughout the recycled Dole Cannery. Each room was designed and staged with the help of a group of improvising performers to afford the participants (up to 150 at a time) a half-hour experience of a different version of Hawaii’s future. Stuart Candy described the event as ‘a sort of theatrical hybrid of theme park ride and role playing exercise.’

Each room depicted one of the four archetypal future scenarios described by the HRCFS: Growth, Collapse, Discipline and Transformation, and how it played out in the context of Honolulu in 2050.

The Growth scenario depicted a live debate between two candidates for Governor of Hawaii in a future where corporations had been granted the rights of personhood. The Collapse room enacted an induction ceremony for climate refugees in a future where Hawaii is run by the military. In the Discipline scenario, economic collapse had been avoided by returning to a back-to-nature communitarian form of society, and the half-hour scenario depicted a Civic Education Center where Hawaiians learned traditional methods of subsisting from the land. Finally, the Transformation scenario took place in a private hospital which offered futuristic body modification options and genetic therapies.

Each of the 530 participants experienced two of the experiential scenarios, followed by facilitated discussions in small groups.

The purpose of the scenarios was to provide the participants with material to inform the discussions, shared reference points for the conversation. The response from participants surveyed after the workshop was extremely favourable, supporting the hypothesis that this kind of immersive experience stimulates both brain and body, leading to richer and more rewarding engagement with the subject.

In his 2010 PhD dissertation, Stuart Candy described the Hawaii 2050 event as only a partial success. Although the popular response to the event was extremely positive, subsequent consultation activities retreated to a much more traditional – and in Candy’s assessment, less effective – form of futures visioning.

Nevertheless, the popularity of the Hawaii 2050 workshop prompted a state legislator to approach the Center in 2011 and asked them to create an experiential futures program for the state government looking at climate change.

Hawaii 2060 was a two-day event run jointly by the Hawaii Research Center for Futures Studies and facilitator Donna Ching. On the first day, the Center created four experiential futures scenarios along similar lines to the Hawaii 2050 event. On the second day, Donna Ching took over as facilitator and held a more traditional butchers-paper-and-pens type workshop, trying to identify preferred futures and pathways to achieve them.

This project resulted in a report which was submitted to the Hawaiian State Government and which led to a piece of legislation requiring all government program and state development projects to include a climate change mitigation strategy.

The success of the Hawaii 2060 event in effecting a change in the state’s legislation prompts interesting reflections on involving the government in these kinds of exercises. Was the legislative outcome the result of the adoption of an experiential futures approach? Or was the involvement of experiential futures practitioners the result of a particularly foresighted group of policy-makers? Either way, the event hints at the importance of policy-maker involvement in projects from an early stage.

These images from the Hawaii 2050 event are from Stuart Candy’s blog – I highly recommend taking a look.

Large-scale trans-media futurism exercise ZED.TO was a nine-month project created by Toronto creative collective The Mission Business over 2012. Explicitly drawing on the principles of experiential futures articulated by the Hawaii Research Center for Futures Studies, The Mission Business used live-action and digital storytelling experiences to engage theatre audiences, game players, and the broader public in an exploration of what it might feel like to live in one possible future.

The central conceit of ZED.TO was the rise and fall of ByoLogyc, a fictional corporation whose synthetic biology and genetic engineering practices evoke the tensions and concerns currently arising from the commercialisation of research into viral therapies and subscription based personalised medicine.

Over the course of the nine month story, ByoLogyc releases a new personalised healthcare platform called ByoRenew — a “software update for your immune system” activated by ingesting a single pill. ByoRenew is sabotaged upon release by an activist organisation opposed to the corporation. The result is a lethal pandemic which quickly spreads beyond the corporation’s desperate attempts to control it.

ZED.TO took place over four key live events throughout 2012, supported by an ongoing and diverse stream of online activity. Public involvement built over the course of 2012 until there were thousands of participants engaging across the spectrum of forms. Each of these ‘performance tentpoles’ mapped to one of the four future images articulated by Jim Dator and the HRCFS:

The first event (Continuation) was an invitation-only launch for the company’s new line of products held in a gallery, offered to a select group of VIPs.

The second event (Transformational), taking place as part of the Toronto Fringe Festival, offered audiences the chance to take part in ByoLogyc’s intern program, giving them tasks and responsibilities within the company and allowing them to sample the company’s products. This event also signaled the initial outbreak of the lethally mutated version of ByoRenew.

The third live event (Disciplined) took the form of an immunisation clinic open to the public during Toronto’s ‘Nuit Blanche’ event, illustrating the corporation’s efforts to contain the spread of the disease.

The final phase of the story (Collapse) was a ticketed performance event for 350 participants taking place in an abandoned brickworks outside the city, which represented the company’s final stand against the outbreak: a kind of corporate concentration camp for victims of the pandemic, defending itself against attacks by the paramilitary wing of the anarchist protest organisation.

The core creative team of The Mission Business coordinated a huge range of creative collaborators and unfolded the story simultaneously through multiple mediums. The success and popularity of the work indicates the effectiveness of the trans-media form and the resonance of the themes.

It is significant that the Mission Business, consisting of artists from live performance and gaming backgrounds, explicitly adopted the strategic foresight methods advocated by futurists in the creation of the work. ZED.TO is perhaps the first major project where ideas from Futures Studies have been put into practice by professional artists, rather than by futurists adopting some artistic practices or creative collaborators.

In his research paper exploring ZED.TO, Mission Business member Trevor Haldenby examines the challenges of manifesting the work as both a rewarding performance experience and as a scientifically informed work of experiential futures. ‘During the production of ZED.TO, I struggled to find a way to transform game-like audience experiences into more rigorous and methodologically aligned research exercises. Sustainably integrating an entertainment experience and research practice is a tall order.’

Nevertheless, it is clear from the dialogue around ZED.TO (captured in online reviews, alternate-reality games forums and personal responses) that the work prompted numerous and thoughtful reflections on the future, and argues for the more central role of artists in constructing meaningful futures scenarios.

The FutureCoast project, created by the PoLAR Partnership at Columbia University and funded by the US National Science Foundation, is a participatory storytelling game that adopts an Experiential Futures perspective.

The FutureCoast website contains a selection of audio recordings, purporting to be ‘voice mails’ recorded between 2020-2065, that have somehow made their way back in time and are audible now. Each message provides a small glimpse into the future it purports to be from, usually focusing on the impacts of climate change.

People are invited to upload their own voice mails to the FutureCoast website, contributing to the bulletin board-style aesthetic of the website.

The strength of large-scale participatory work such as this is that it offers a porous space for public engagement. It can be challenging, however, to curate and maintain a quality standard across this platform. Nevertheless, FutureCoast experienced a high uptake in both contributors and audiences.

A very different approach is advocated in the course summary for the University of Hawaii’s Underground Futures Studies degree*: ‘Guerilla Futures: systematically picture how alternative worlds could unfold; manifest your own visions playfully and compellingly in a range of media; and make these narratives available in the real world, via live urban interventions for unsuspecting audiences to encounter.’

The result of these Guerilla Futures projects often include street art referencing events that haven’t happened yet, installations in public spaces (often including ‘future artifacts’) and occasionally, monuments to future tragedies or achievements.

Along similar lines are the Blue Line Projects, which have been carried out in various cities around the world. The execution varies but the core idea is quite simple: a blue line is traced (using chalk, or paint, or tape, or sometimes projected) through the streets of the city, showing where sea level is expected to be by the end of the century if global warming continues.

Where they have sought city approval, these projects have often experienced severe backlash from real estate developers, property councils and other businesses who may suffer financially if waterfront properties are perceived to be less permanent. However, the simplicity of the project means that it can be carried out with virtually no resources and planning by community groups and activists.

In one such example in Santa Barbara, where the property council’s aggressive reaction resulted in the community group being refused permission for the project, anonymous activists protested the decision by drawing the line anyway. The end result, thanks to the controversy and public debate, was that the population of Santa Barbara became significantly more aware of the implications of sea level rise for their city.

The immediacy of this kind of work for the viewer really captures some of the essence of the Experiential Futures tag. Though the nature of guerilla art means that most passers-by do not engage with it, those that do engage will experience these ideas in a very unusual context, and the simple fact of their surprise may stimulate them to reflect on and consider these ideas more thoughtfully than if they had read them in a book or seen them in a TV documentary.

*Now also, I’m pleased to see, being offered at OCAD University in Toronto, by none other than Stuart Candy.